Quasisymmetry

A hidden symmetry of magnetic fields that enables confinement

In a stellarator, even if the magnetic field lines lie on nested toroidal surfaces (“flux surfaces”), some particles may still not be confined. Charged particles do drift off of field lines even in the absence of collisions and turbulence, associated with the fact that the magnetic field B must have gradients. Stellarator shapes must therefore be optimized to ensure these cross-field drifts do not allow particles to travel out of the confinement region. A solution to this optimization problem is provided by quasisymmetry, a remarkable property of some magnetic fields that ensures the drift across flux surfaces has a time average of zero.

To understand qasisymmetry, first consider axisymmetry, meaning standard continuous rotation symmetry. In a truly axisymmetric magnetic field, conservation of canonical angular momentum ensures that the drift across surfaces averages to zero over time, so a particle’s departure from a particular magnetic surface is small and bounded. But this cross-field drift can also average to zero in the absence of true axisymmetry, due to a remarkable result: once the fast gyration of particles about B is averaged over, canonical angular momentum conservation requires only a continuous symmetry of B=|B|, the magnitude of the field, not of the full vector B. Such a symmetry of B is called ‘quasisymmetry’. Non-axisymmetric magnetic fields, even if they are integrable, are generally not close to being quasisymmetric. However, using optimization, magnetic fields have been found that lack true axisymmetry but approximately possess both integrability and quasi-symmetry. One stellarator of modest size that has been built on this principle, the Helically Symmetric Experiment (HSX) at the University of Wisconsin, has experimentally demonstrated the benefits of quasisymmetry. Other quasisymmetric stellarators that have been built include MUSE at the Priceton Plasma Physics Laboratory and CFQS in China.

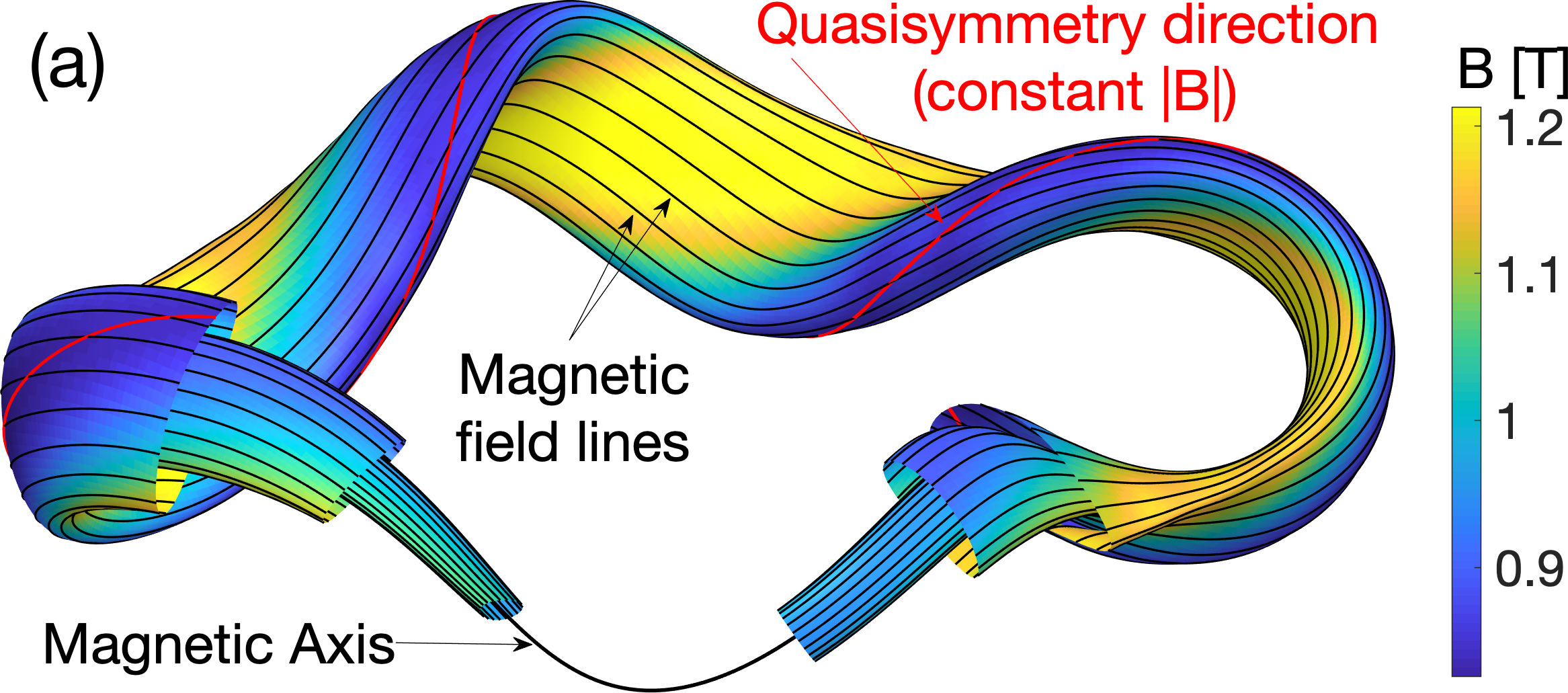

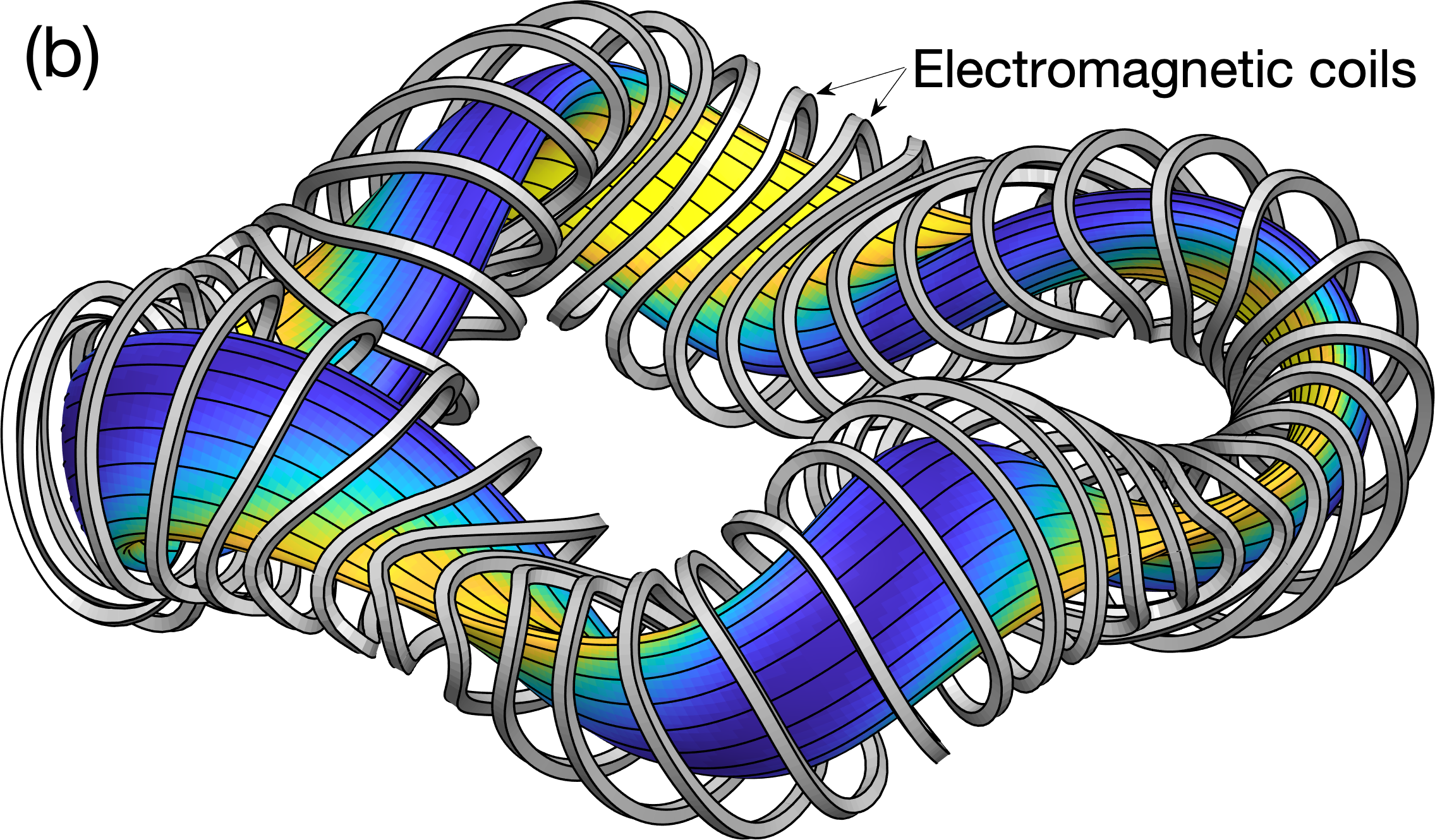

Figure 1 shows an example of a quasisymmetric magnetic field. Figure 2 shows the same configuration along with the electromagnetic coils that produce the field.

A more detailed introduction to quasisymmetry can be found here.

Our group has developed several methods for finding quasisymmetric magnetic field geometries. One is an optimization procedure which allowed a far higher degree of quasisymmetry to be achieved than previous approaches. The results of this procedure are known as the precise quasisymmetry fields, and have become widely used examples in the community. In this approach, with a 1 Tesla mean field far from axisymmetry, quasisymmetry-breaking mode amplitudes throughout a significant volume can be made as small as the typical ∼50 𝜇T geomagnetic field. PhD student Byoungchan Jang recently improved the optimization procedure to be more efficient and reliable, described in this publication.

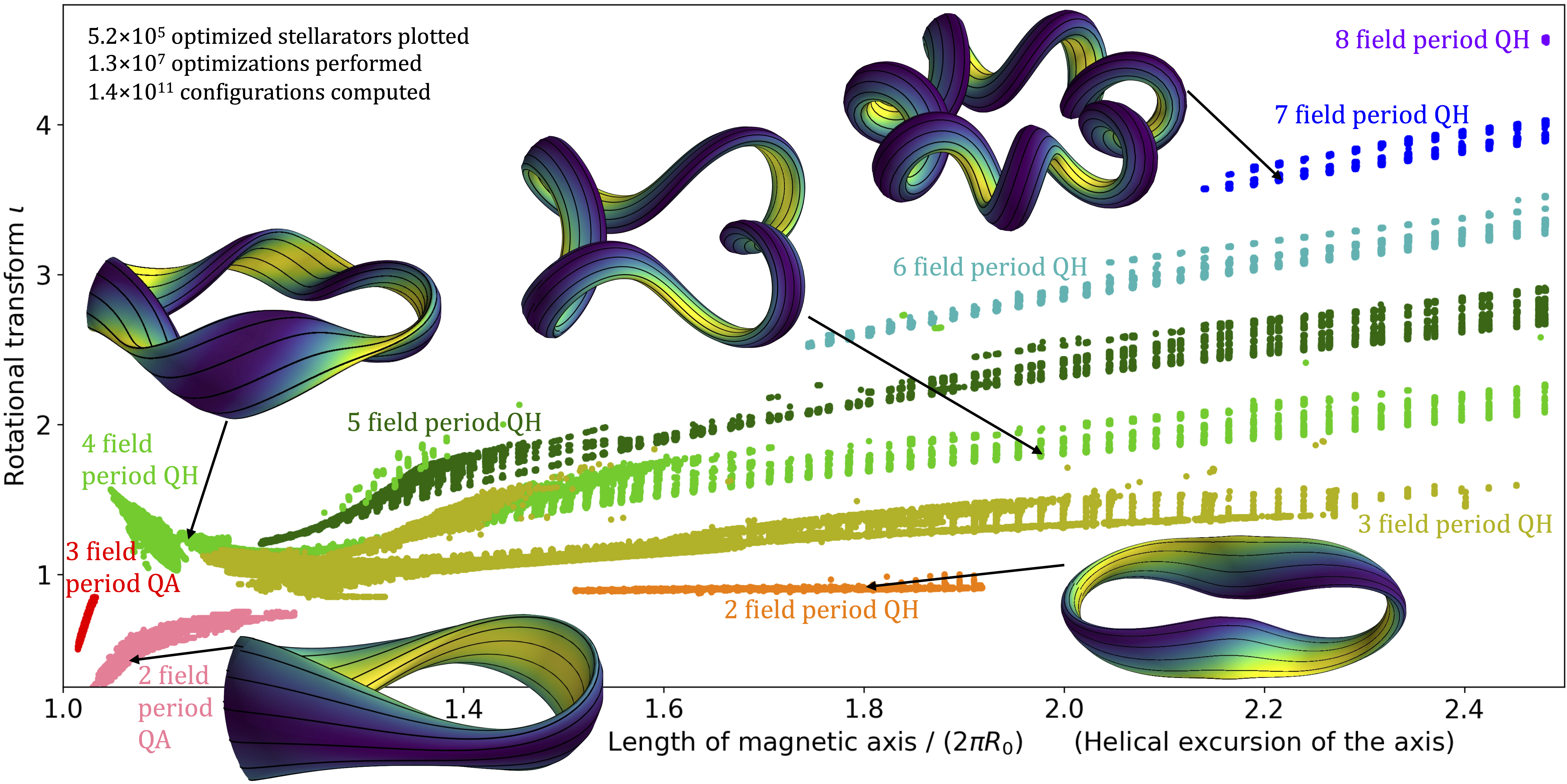

Our group has also developed another method to find quasisymmetric fields based on asymptotic expansion which is extremely fast. In this approach, we focus on the region close to the magnetic axis, which is the innermost magnetic field line, shown in figure 1. The equations of magnetohydrodynamic equilibrium and quasisymmetry can then be expanded in a small parameter: the distance from the magnetic axis compared to the scale length of the axis (e.g. a typical radius of curvature). This expansion, which is sometimes called a high-aspect-ratio approximation, represents the fact that the core of a stellarator looks more like a skinny bicycle tire than a fat monster truck tire. This expansion is accurate in the core of any stellarator, and it allows the equations of quasisymmetry to be solved in times on the order of a millisecond. Through this near-axis expansion approach, it has been possible to extensively map the space of possible quasisymmetric fields as shown in figure 3, discovering new classes such as 2-field-period quasi-helical symmetry.