Magnets

Designing the shapes of electromagnetic coils and other magnets to realize fusion devices

A central issue for any magnetic fusion concept is the calculation of the shapes of magnets to produce the confining magnetic field. Magnetic fusion devices always include electromagnetic coils, and permanent magnets or diamagnetic blocks could be included as well. The design of stellarator magnet shapes has close analogies in other subjects, such as the design of electromagnets for magnetic resonance imaging and particle accelerators.

While the problem of computing the magnetic field B from known currents J is straightforward, the problem of computing the currents to produce a desired field is an ‘ill-posed inverse problem.’ This means that an infinite number of different current distributions can produce almost exactly the same field in the confinement region. The ill-posed nature of the stellarator coil design problem is actually an advantage, in that it means there is substantial freedom in the magnet design that can be exploited.

Our group researches several aspects of magnet design optimization, many of which are applicable not only to stellarators but also to other magnetic fusion systems. Improvements in this area can have significant impact on the feasibility of building a fusion device, since the coils are among the most expensive and difficult components to fabricate.

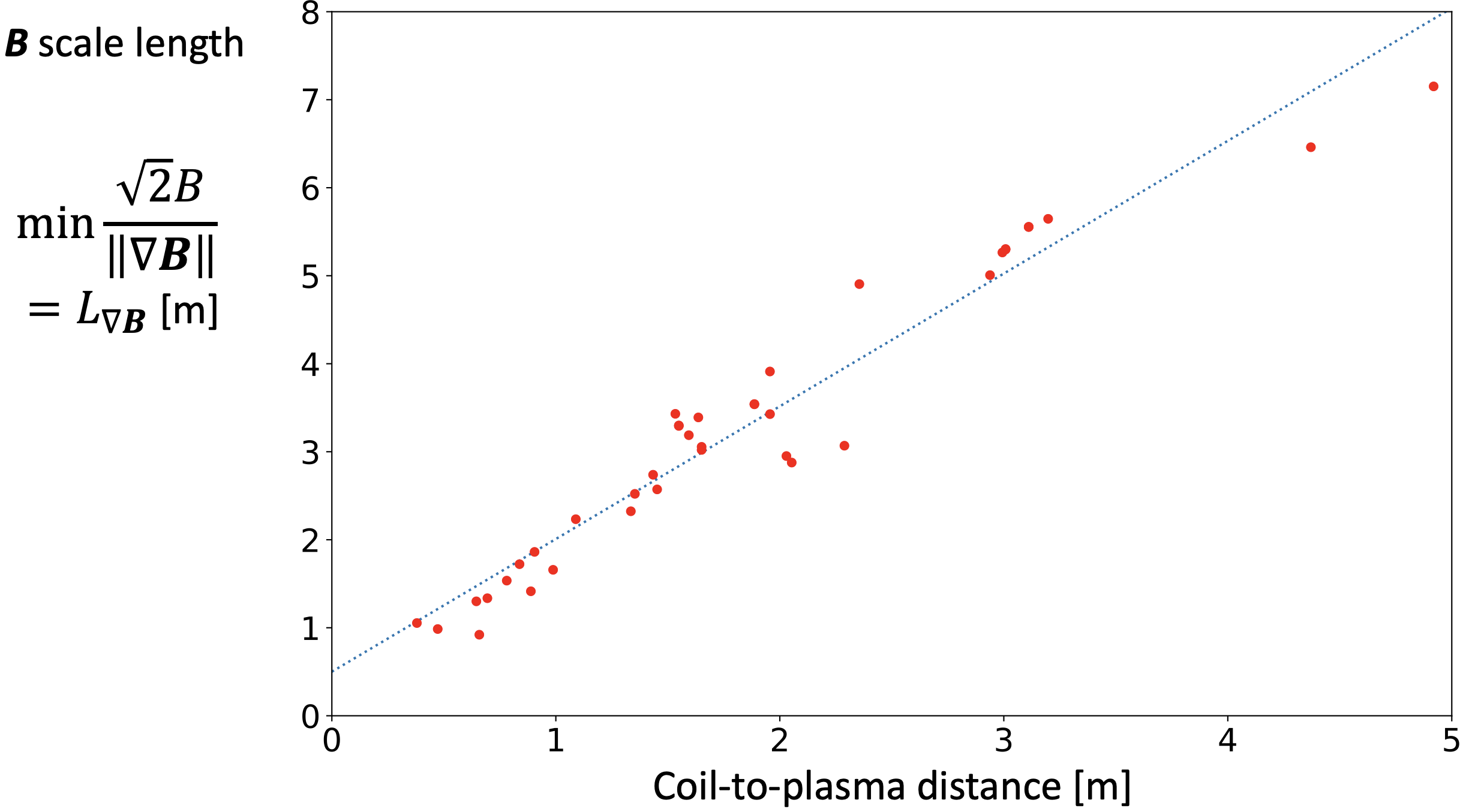

Understanding coil complexity from the B scale length

It is important to have enough space between the plasma and coils to fit several components in between. For many stellarators it has been observed in practice that coils cannot be designed beyond a certain distance from the plasma, and this threshold distance can be quite different from one plasma geometry to another. In a recent paper, PhD student John Kappel from our group explained these phenomena using the scale length of the magnetic field. The notion of a scale length is widely used throughout physics. In the stellarator context, if the magnetic field in the confinement region has a scale length L, intuitively it will be hard to create this magnetic field pattern with magnets that are more than a few multiples of L away. John showed that indeed there is a very strong correlation between the magnetic field’s scale length in the plasma and the maximum achievable coil-to-plasma distance, figure 1. This finding not only allows us to understand this fundamental constraint on stellarator design, but it also enables optimization of plasma shapes for increased coil-to-plasma distance and reduced coil complexity, improving engineering feasibility. Following our publication, the magnetic field scale length has been adopted by companies including Proxima Fusion and Type One Energy in the design optimization of their devices.

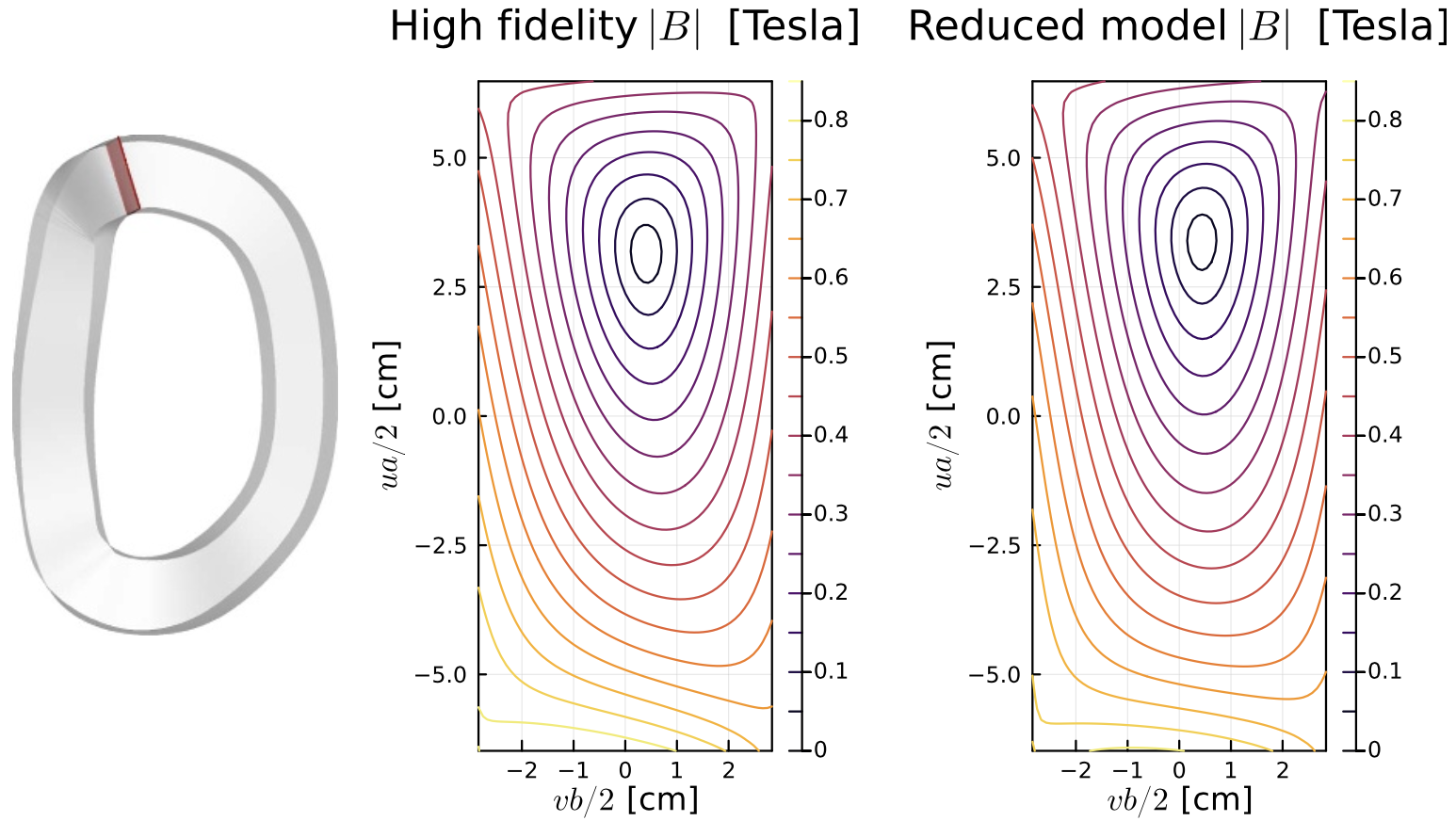

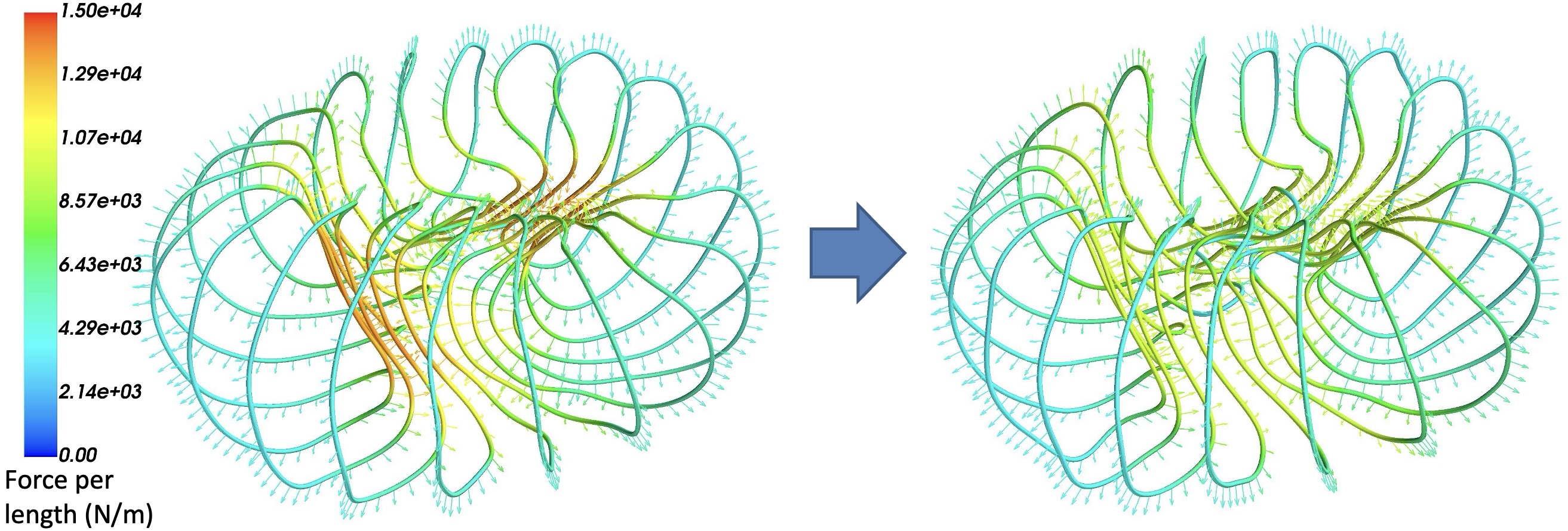

Self-fields and self-forces on electromagnets

One concern for magnetic fusion systems is the large Lorentz force on the coils. Another concern is the field strength inside the magnets, which determines the critical current for superconductivity. For these force and internal field calculations, the coils cannot be naively approximated as infinitesimally thin filaments due to divergences when the source and evaluation points coincide, so more computationally demanding calculations are usually required, resolving the finite cross-section of the conductors. Our group has devised a new alternative method that enables the internal magnetic field vector, self-force, and self-inductance to be computed rapidly and accurately within a 1D filament model, Figure 2. The reduced model is derived by rigorous asymptotic analysis of the singularity, regularizing the filament integrals such that they match the true high-dimensional integrals at high coil aspect ratio. This work is led by PhD student Siena Hurwitz, and has been presented in several recent papers: Hurwitz (2023), Landreman (2025), and Hurwitz (2025). In the last of these, Siena demonstrated that the reduced model allows for Lorentz forces to be reduced using derivative-based coil shape optimization, Figure 3.

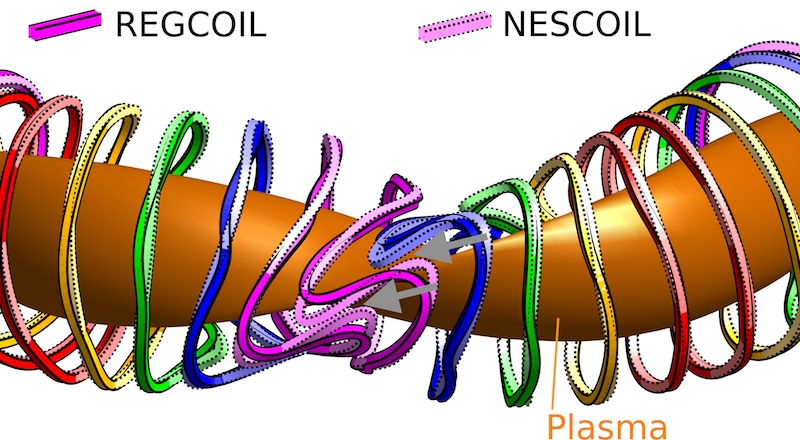

Magnet design algorithms

An example of an improved coil design formulation developed in our group is the REGCOIL method, described in this paper, and implemented in the code here. In REGCOIL, the inverse problem is regularized using a physical term – the inverse distance between coils. As a result, coil shapes computed by REGCOIL have larger spaces between the coils, improving the feasibility of designs and leaving more room for ports. Figure 4 shows the superiority of REGCOIL-derived coils compared to coils from the earlier algorithm used to design the coils of W7-X and HSX, NESCOIL.

Questions

Our group is pursuing several research questions related to magnet design. How can ferromagnets, magnetic materials, and/or diamagnets be incorporated into fusion system design? To what tolerances must the coils be built, and how can we design stellarators to make these tolerances wider? How can stellarator design be formulated such that the resulting coil shapes are as simple to build as possible? How can we compute magnet shapes that provide significant experimental flexibility?